Rhythm

Rhythm

Rhythm is everywhere. There’s rhythm in the music you listen to. There’s a rhythm to the way you talk, and the way you move. The motor in your car has a rhythm. The cycle of day and night follows a rhythm. The phases of the moon follow a rhythm. As human beings, we’re conditioned to identify and internalize rhythm.

As a visual artist, you can exploit this natural affinity for rhythm with line and shape to lead your audience’s eye through your work. As an animator, a basic understanding of rhythm will allow you better control of your timing and therefore better control your audience’s experience. Finally, as a martial artist, rhythm is a means of prediction and deception you can employ to disrupt your audience’s timing and punch him in the face[1].

I’m going to give a quick crash course in music notation so we can all be on the same page in terms of talking about rhythm. Then I’m going to split off in two separate tracks and explore rhythm in animation, and rhythm in martial arts.

Rhythm vs. Time

In music, there’s a distinction between measuring rhythm and measuring time. You can see this on display when a crowd of people starts clapping in unison. Even if it’s just a simple rhythm, clap clap clap clap, they’ll usually start speeding up the longer it goes on. The Rhythm is that simple clap clap clap, and they’re handling that with no problem. But the Time is a problem for them. They can’t keep it consistent (and the error is always in the direction of speeding up).[2]

Rhythmic Notation

Rhythmic notation is a way of communicating a measurement of time.[3] It’s just like counting seconds on your watch, days on your calendar or, for you Animators, frames of film. Each of those things represents a unit of time.

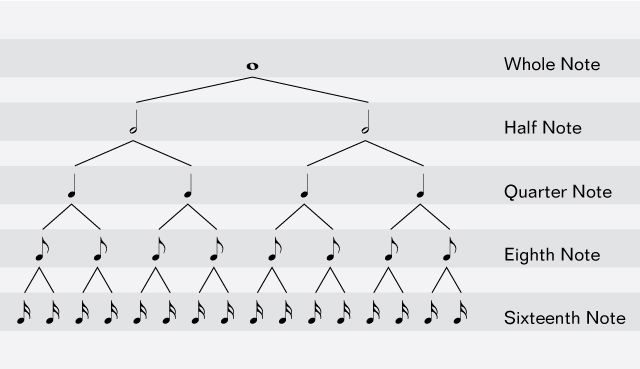

To create various rhythms, we use different notes to represent different lengths of time relative to each other. It’s just like measuring one second, then a half second, then a quarter second, and so on. In music, we would say you have a Whole Note, a Half Note, a Quarter Note, an Eighth Note, and on and on.[4]

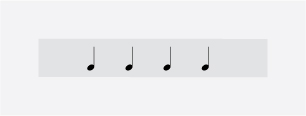

So that basic rhythm of a crowd clapping in unison would look like this:

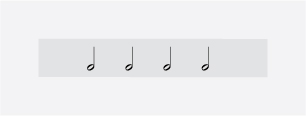

But remember, we’re only talking about Rhythm and not Time. So the same rhythm could be written as four half notes:

Or even as four eighth notes:

The rhythm is just the duration of the notes relative to each other. That’s why we can substitute Quarter Notes or Half Notes or Eighth Notes or whatever. It’s all only in context of each other. We have no idea how fast it should be played so we can pick any four notes that are equal in length.

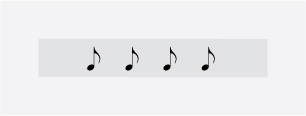

Here’s a simple rhythm that’s just slightly more complicated:

Together, the first two notes fill the same amount of time as the third note does by itself. If you put it in context of a song most people have heard it would sound like this:

The clap takes just as much time as the two stomps that precede it.

The last thing I’ll mention about notating Rhythm is that, in addition to symbols which indicate a note of a certain length, we also have symbols that indicate an empty spot of certain length. These are called “rests” and follow the same structure of endlessly smaller halves that the notes followed:

Time

Time is relatively unimportant for the purposes of applying Rhythm to Animation or Martial Arts, but defining how Time is notated will allow us to look at rhythms in bite sized chunks. I don’t know if this will come into play in later blog posts, but here’s a similarly quick-and-dirty definition of that notation just in case.

Imagine reading a book without punctuation. There are no periods so every sentence just runs into the next. You don’t know when any idea starts or stops. It just becomes a stream of words.[5] So we need a way of organizing a group of notes into a sentence. In music, the equivalent of a sentence is called a “Measure.”

Measures, just like sentences, can come in different sizes. Some are short. Others wander around the barn and back, covering myriad ideas and topics, eventually landing on several different concepts but leaving the audience, if there still is one considering how long and boring the sentence was, wondering how they got there.

To define how many notes we can cram into a Measure we need to define how big that Measure is. We do this with what’s called a Time Signature. A Time Signature consists of two numbers.

- The bottom number defines what type of note gets one “beat”. A Half Note would be a 2; a Quarter Note would be a 4; an Eighth Note would be an 8; a Sixteenth Note would be a 16.

- The top number defines how many beats fit in one Measure.

If a Quarter Note gets one beat and you have four beats per Measure, you’d have 4/4 time:

If a Quarter Note gets one beat and you have two beats per Measure, you’d have 2/4 time:

If you had six beats per Measure and an Eighth Note gets one beat, you’d have 6/8 time:

Here are a couple of examples of complete measures with an appropriate rhythm inside that measure. Remember, just because a Quarter Note gets one beat doesn’t mean you can only use a Quarter Note. It means you must fill the equivalent amount of space as one Quarter Note.

What’s Next?

Now that we have a common framework for talking about Rhythm, the next thing I’m going to do is discuss applying that knowledge to the two main subject areas I’ve been writing about: Animation and Martial Arts.

[1] Your opponent in a fight is really just another type of audience.

[2] Technically, you could say the person speeding up gradually has bad Rhythm as well because they’re short changing the spaces between notes ever so slightly. But what I’ve noticed over the years leads me to believe it’s a different attribute that causes a person to have Good Time versus Good Rhythm.

[3] Not to be confused with the capital-T Time I’ll be talking about later.

[4] Theoretically, this halving goes on forever but that’s a little silly. I think the fastest note I’ve ever seen on a legit piece of music was a 128th Note.

[5] As a side note, the actor Christopher Walken only works from scripts that have all the punctuation removed. That’s partly responsible for his unique, stilted way of delivering dialogue.