Animators and martial artists both must study movement. However, the difference between the two is when an animator expresses that movement they do it externally, and when a martial artist expresses a movement they do it internally. This is probably appropriate because I don’t think we want a bunch of animators walking around the studio punching people in the face. Well, maybe sometimes. Regardless, there’s another problem here.

Animators and martial artists both must study movement. However, the difference between the two is when an animator expresses that movement they do it externally, and when a martial artist expresses a movement they do it internally. This is probably appropriate because I don’t think we want a bunch of animators walking around the studio punching people in the face. Well, maybe sometimes. Regardless, there’s another problem here.

If an animator has a scene with Character A punching Character B in the face, the animator is not directing Character A to actually punch Character B in the face. The characters are just pixels or pencil lines anyway. What the animator is really trying to do is convey to the audience the idea of a punch in the face.

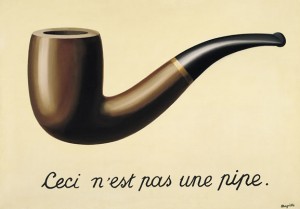

This isn’t a new concept. René Magritte addressed the issue in The Trechery of Images in 1929. Where animators can run into trouble is also the intention of an actual martial artist versus the need to communicate a martial arts technique.

If I’m punching someone in the face, I want to give that person the least possible clue what I’m about to do. To have a high chance of success, the punch needs to take the target by surprise. We call this being “non-telegraphic.” Unfortunately, this is exactly the opposite of what animators are taught to do. We animators are taught to include anticipation in a movement: retract before you extend, go left before you go right, sink before you rise, and so on. The anticipation gives the audience a visual clue what’s about to happen and allows fast actions (like fights) to read better.

Now, I think animators who animate a lot of fights should go train some martial art somewhere. It doesn’t really matter what system. What’s important is the chance to internalize these movements. But I understand this isn’t for everybody so here’s how I approach looking at video reference.

One of my teachers, Sifu Louis Campos, has a great approach to working individual techniques:

- First, you work that technique in isolation. For example, do 100 jabs (lead hand straight punch) on the heavy bag.

- Next, you work that technique in combinations. For example, jab-cross-jab, jab-cross-hook, jab-cross-uppercut, etc.

- Then you incorporate that technique into sparring (low intensity “fighting” with a training partner).

That’s a never ending cycle for the martial artist. But the animator can follow the same sort of pattern. Instead of jumping in and finding reference of a really awesome fight from a live action movie, look for individual techniques first. YouTube has become a great resource for this sort of thing. If you search for Boxing Jab Technique, you’ll get about 2,000 hits of people breaking down the jab.

After you get a sense of the component movements of that technique, you can start thinking about adding anticipation or offsets so it reads better to the audience. Then proceed to the next step and find some reference of an instructor teaching it in combination with other techniques. Once you see how the techniques flow from one to the next, you’re ready to look at that sweet Hollywood fight choreography. But without understanding the mechanics of individual moves, you’ll be hard pressed to decipher what’s happening in a fight.

At the end of it all, remember this isn’t a real fight. This is the idea of a fight. 100% technical accuracy isn’t the goal. It doesn’t have to be right it just has to look right.